Modern football fans are smart,

and they keep getting smarter. Most people who watch football on a regular

basis know what you’re talking about when you refer to a blitz, or to play

action, or to a nickel defense. Commentators are going more in depth with their

analysis every year, and the growth of internet blogs like this one has made

it easier for fans to find in depth analysis. But there is still so much more

about football out there, so much that even I don’t fully understand. This is a

beautifully complex game, with nuances of technique and scheme that most fans

aren’t aware of. So strap yourselves in as I take you on a highly technical

tour of NFL defenses.

Note: As I said above, I don’t

know everything. I never played football above a high school level, and several

of the things I’m discussing below were never handled in my high school’s

defense. It is very possible that some of my readers know more than me on these

topics. If I’m wrong about something, feel free to leave a comment so I can

correct it. I would love nothing more than to learn even more about football.

Linemen Positioning

The terminology for the

positioning of defensive linemen has been around in football for decades, but

it has only recently become common in the vocabulary of casual football fans.

It is a fairly straightforward numbering scheme, shown the diagram

below. The numbers increase out in a mirrored pattern from the center. The even

numbers represent a defensive player lining directly in front of an offensive

lineman—0 for the center, 2 for a guard, 4 for a tackle, and 6 for a tight end

(if present.) The odd numbers fill in the gaps in between, though they

technically refer to the outside shoulders of the respective linemen. As you

can see, the numbers get a little messed up out around the edge, but on the

interior it is mostly easy to figure out. Teams sometimes focus on finer

details and will add the letter “i” to an even number to indicate the inside

shoulder of an offensive linemen.

This terminology has been used in

several contexts over the past few years. The most common is when describing

the smaller, quicker defensive tackle in a 4-3 scheme. This defensive tackle is

commonly known as “the 3-technique” since that is where he lines up in most

normal alignments. Another common usage is when discussing a defensive end in

the “Wide 9” position. As the name suggests, this indicates an end lining up

far outside the tackle box. This offers a lot of advantages as a pass rusher,

but it takes the ends out of the run game, opening up a massive lane for backs

to run through. To play this sort of defense a team needs extremely stout

linebackers, and it is normally used only in obvious passing situations.

One Gap

There are two main techniques

employed by defensive linemen. The first and simplest of these is “one

gapping.” A one gap scheme is all about pressure, relying on a defensive

lineman to control a single gap by penetrating into the backfield. Linemen in

this scheme are usually required to be explosive off the ball and to know how

to disengage with blockers off initial contact. They are typically smaller and

quicker than linemen who engage with blockers. Most of the linemen who

consistently make plays in the backfield do so running a one gap scheme,

allowing them the freedom to be aggressive and use their speed to shoot past an

offensive lineman.

As you would expect, one gapping

has its strengths and weaknesses. It can blow up traditional running schemes,

penetration often making it impossible for backside linemen to pull around and

contribute to the play. But it can cause problems against a zone running

scheme, where blockers are perfectly content to let a defender run himself out

of the play to give the runner an open lane to cut through. The one major advantage one gapping

offers is against the pass, where penetrating defensive linemen can present

quick pressure in the face of the quarterback. Edge pressure causes plenty of

problems, but pressure directly in front of the quarterback can be even worse,

giving him no time to make decisions and preventing him from being able to see

downfield.

Two Gap

Two gapping

is essentially the opposite of one gapping. In this scheme a defensive lineman

is responsible for both the gaps on either side of him, and it is up to him to

prevent the blockers from pushing him in a way that he can’t engage with a

runner coming through either gap. He needs to use his size and his hands to

establish control off the snap of the ball, standing the opposing lineman up

and trying to push him into the backfield rather than trying to run around him.

If he can gain proper control, he should be able to cast the blocker aside in

either direction once he knows where the play is going.

Two gapping is what most people

think of when they imagine defensive linemen, particularly defensive tackles.

It requires someone who is big and stout (aka fat) to hold his ground and to

allow the linebackers to scrape through the holes. It prevents the defensive

linemen from making many plays, but it allows for a more cohesive, technically

sound defense. It

doesn’t provide much in the way of a pass rush, but the best defensive tackles

can shove linemen back to collapse the pocket, giving the quarterback less room

to escape from the edge rushers.

Stunt

There is another important

technique used by the defensive front that I need to bring up, and that is

stunting. A stunt is a called play intended to confuse an offense’s blocking

scheme by switching the responsibilities of the defenders. The simplest form of

a stunt is a cross, as shown in the image below. One lineman—in this case the

defensive end—will crash hard across the blocker beside him, shooting into the

gap between him and the defensive tackle. His goal is to draw the blocker ahead

of him towards this gap while the tackle loops around and races through the

open hole. The lineman responsible for the defensive tackle won’t be able to

fight through the muddle, and unless his teammate can recognize and make the

switch the defensive tackle will have a clear lane into the backfield. If he’s smart about

it, the defensive end can even get away with grabbing hold of the outside

offensive lineman to prevent him from sliding out and picking up the defensive

tackle.

There are many varieties of

stunts between the line and the linebackers. A crashing defensive linemen will

often try to occupy two blockers while a linebacker blitzes in behind him.

Stunts are effective against either the run or the pass, though they can also

create easy leverage for an offensive lineman to use in the running game. They

are better off used by teams without elite defensive linemen, who struggle to

win individual matchups. If at all possible, teams are probably better off just

letting their defensive linemen play the gaps in front of him.

3-4 vs 4-3

There has been a lot made about

the differences in defensive schemes. Whenever a team struggles on defense,

they usually bring in a new coach who promises a switch to a new alignment,

exciting fans over all the possibilities. In truth, there is very little

functional difference in schemes any longer. Traditionally, the 3-4 defense

asked its defensive linemen to play primarily as two gappers, leaving its

linebackers free to make more plays. But as the passing game has grown, 3-4

teams have begun to ask for more penetration from their defensive linemen,

leading to the development of playmaking 3-4 ends like JJ Watt and Muhammad Wilkerson. And

now that teams play most of their snaps with nickel personnel both schemes end

up looking a lot alike.

Here’s Washington, a 3-4 team in

the nickel.

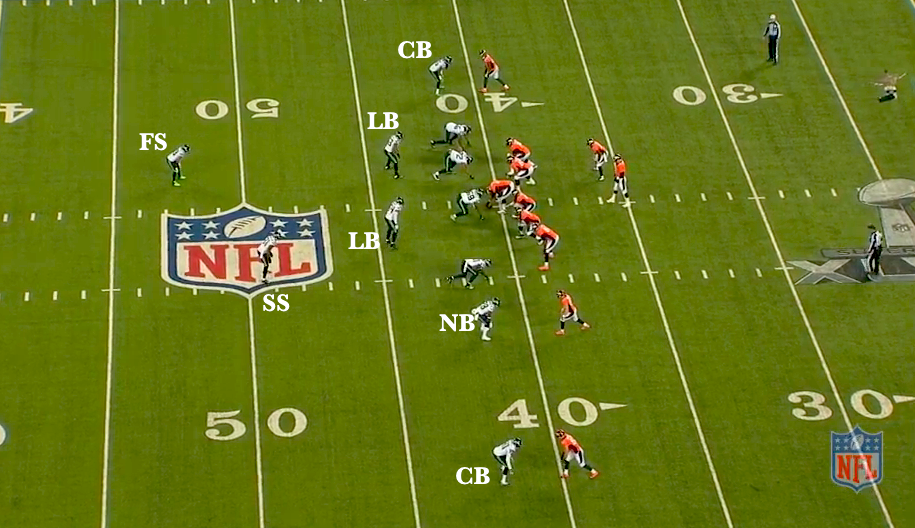

And here’s Seattle, a 4-3 team in

the nickel. See the difference?

When going to the nickel, a 4-3

team normally takes a linebacker off the field. When going to the nickel, a 3-4

team normally takes a defensive lineman off the field and moves their edge linebackers

up onto the line. The only difference is whether the outside players go down

into a 3-point stance or remain standing in a 2-point stance. So the next time you hear someone

freaking out about the change from a 4-3 to a 3-4 or vice versa, try not to

laugh too hard.

Zone Blitz

Blitzes have been around since

the beginning of football, and most casual fans understand how they work. At

the snap of the ball one of the linebackers rushes towards the line of

scrimmage, attempting to shoot into the backfield to disrupt the play. Normally

linebackers are supposed to read and react, but on blitzes they become

aggressors like the linemen in front of them. Blitzes are useful for creating

pressure on the quarterback and for breaking down the blocking scheme of a

running game.

There is one major downside to

blitzing on a pass play. Bringing an extra rusher means one fewer man in

coverage, and for a team that wants to play a zone coverage scheme this puts an

extra burden on every defender on the field. No offensive line can hold against

a blitz indefinitely, but if they can weather the initial rush the quarterback

usually has time to find a hole in the zone. Normally teams try to avoid this

by playing man coverage, but in the past couple decades teams have found a way

to disrupt pass protection without sacrificing the ability to play zone.

The sneaky secret behind a zone

blitz is that it often isn’t technically a blitz. Like a normal blitz, one of

the linebackers will rush into the backfield at the snap of the ball, leaving

the other defenders behind him to play in coverage. But unlike on a normal

blitz, on a zone blitz one of the defensive lineman will not rush the passer.

Instead he will drop back into coverage, filling the zone that would normally

be taken by the linebacker. The decrease in coverage ability is made up for by

the confusion sown by the presence of the extra rusher and the man dropping

into coverage where the quarterback isn’t expecting him, leading to plays like

the one below.

Coverages

There are three primary

categories of coverage schemes, all with names that make it pretty clear what

they are. The number describes how many zones the deep portion of the field is

split into, zones usually patrolled by safeties or cornerbacks. I don’t have

the knowledge or the space to go into the full details of the coverages, so I

will instead focus on the three largest blanket categories. Each of these is

just one part of a coverage scheme, and they can all be played with varying

schemes in the underneath portions of the field.

Cover 1

Cover 1 is the most popular

coverage currently used in the NFL. A single safety will sit in the deep middle

of the field, reading the quarterback to decide how to take away the top half

of the defense. This frees a team’s second safety to drop down into the box for

run support or to bounce outside to match up with a receiver in the slot. Cover

1 normally works best with man coverage underneath. Dividing the field into

zones can take away almost every passing lane underneath, but there are very

few safeties who can cover sideline to sideline in the deep zone. Most teams

are better off matching up man to man across the board, relying on the single

safety as a backup option in case the receiver beats his man deep.

Cover 2

Cover 2 is the most varied of all

the coverage schemes. It is possible to play with either man or zone coverage

underneath, and it is often used when a defense wants to try to disguise what

it is doing from the quarterback. It offers plenty of protection in case of

breakdowns, but it doesn’t take too many defenders away from the shorter

portions of the field.

The scheme most commonly

associated with Cover 2 is one that has fallen out of favor in recent years:

the Tampa 2.

Spread through the NFL by Tony Dungy and his assistants, it uses two safeties

deep to patrol the outside of the fields while the cornerbacks sit in the flats

to take away quick passes. The weaknesses of this scheme are down the middle of

the field between the two safeties and on the sidelines in the window between

the cornerbacks and the safeties. Ten years ago this was the most popular and

most successful system in the league, but offenses have adapted to attack these

vulnerabilities, leading to a trend towards more man coverage. Plenty of teams

still use Cover 2, but they use it in a different way than they did a decade

ago.

Cover 3

By now you can see the pattern.

Cover 3 divides the field into three deep zones, usually handled either by a

pair of cornerbacks and a safety—leaving the other safety free to roam—or by a

single cornerback who rotates back to cover beside the two safeties. It is very

difficult to complete deep passes against this defense, short of sending four

receivers all running down the field together (which is actually a far better

play than you would think.) Most teams that use this scheme employ a zone

underneath. Playing man to man would leave only three defenders available to

rush the passer, though teams sometimes still send four if they aren’t worried

about the running back leaking out of the backfield.

Seattle’s Cover 3

There are countless variations to

the basic coverage schemes I listed above, but Seattle’s version of the Cover 3 is one that

I want to bring particular attention to. Seattle’s

dominance on defense owes a lot to the fantastic players that make up that side

of the ball, but just as much credit needs to go to their scheme, one of the

most innovative and inimitable in the NFL. Their primary defense is a form of

Cover 3, but they have enhanced it by playing press coverage with their outside

cornerbacks before asking them to drop into deep zones. This takes away many of

the quick passes to the outside that teams commonly use to exploit Cover 3

defenses, giving their linebackers additional time to drop into the flats while

the cornerbacks float back into the deep corners.

This scheme is very difficult to

beat, but it only works because of the discipline and athleticism of the

players in it. Seattle

has one of the most athletic linebacker corps in the game, allowing them to

keep their linebackers in the box without leaving themselves vulnerable in the

flats. The length and athleticism of their cornerbacks makes it easier to play

press coverage and to recover when a receiver manages to slip the initial

press. Even when one of their cornerbacks is beaten deep, the window for a

quarterback to throw the ball over their outstretched arms is very small. And

most importantly, they have the best cover safety in the game in Earl Thomas.

Thomas is fast and smart, and he’s been coached up by Pete Carroll, who has

been known for decades as one of the best defensive back coaches in football.

Other teams are now implementing parts of this scheme into their defense, but

it is highly unlikely that any will be able to replicate Seattle’s success.

No comments:

Post a Comment