A little over a week ago I took a more in depth look at several facets of NFL defenses. This week I'm taking a look at the offensive side of the ball, with one small special teams matter thrown in for good measure. So prepare yourself for another dry but illuminating 3000 words. If you can make it through, congratulations.

Illegal Formation

This is one of the simplest parts

of the game, but it seems to be one that the average fans haven’t quite figured

out. The rules are fairly straightforward. An offense has eleven players on the

field, seven of which must be lined up along the line of scrimmage. The other four players, including the

quarterback, all have to line up back away from the line of scrimmage. The purpose behind

these rules is to clearly define who is an eligible receiver. Anyone off the

line of scrimmage is eligible, as are the two players on the outside ends of

the seven on the line. The five interior players are ineligible and cannot be

targeted with a pass. (As is the quarterback when he takes a snap under center.

He is eligible if he takes the snap from shotgun. Don’t ask me why.)

There are a few ways illegal

formation penalties happen. The first and most common is when a wide receiver

who is supposed to be on the line of scrimmage lines up too far back, leaving

only six players along the line.

Similarly, an infraction can

occur if a receiver who isn’t supposed to be on the line of scrimmage lines up

too far forward, giving the team eight players across the line. Sometimes the

referees will not call this penalty, instead throwing a flag if the covered

receiver attempts to go out on a pass. This can lead to a player being flagged

for a penalty even if he did everything correct because one of his teammates

moved up on the line beside him.

The final common way to get an

illegal formation called is if an offensive lineman isn’t far enough up towards

the line of scrimmage. It is often advantageous for a tackle to sit as far back

as possible to cut down the angle a pass rusher has to the quarterback.

Sometimes the tackle will get too far back, leaving the team with only six

players along the line of scrimmage.

Pulling

Pulling is a fairly

straightforward concept that most fans are probably familiar with. The purpose behind pulling is to create a numerical advantage

by bringing an extra blocker from the backside of a running play around to lead

block for the runner. This is done by having the lineman step backwards from

the line and run through the clear space behind the other blockers, either

kicking out a defender directly in front of him or turning upfield to go after

a linebacker. Most of the time when you see a lineman pulling it is the

backside guard, though occasionally you will see a tackle, a center, or even a

playside guard pulling to block for a run towards the sideline.

Pulling is one of the most

important parts of an offensive scheme, but it may be even more important to

the defense. A pulling lineman almost always leads in the direction of the

play, and it is one of the most crucial keys for linebackers and safeties

attempting to read where the play is headed. The removal of a blocker from one side

of the line also opens up a hole for a penetrating rush, and a quick defensive

lineman can follow the guard down the line and make a play in the backfield.

The extra blocker still makes it worthwhile for offenses

to pull their linemen, but defensive players are very skilled at taking

advantage of such a strategy.

Zone Blocking

Most run blocking schemes make

each offensive lineman being made responsible for a specific man. There are a variety of

arrangements involving pulling, double teams, and reach blocks, but in most

cases offensive linemen come to the line, identify who they are responsible

for, and find a way to seal that player off from the direction of the run. Zone

blocking is the major exception to this, and over the past twenty years it

has grown into a full scale offensive scheme of its own. A zone blocking scheme

makes the linemen responsible for areas of the field rather than individual

players, trusting that lanes will naturally emerge and running backs will make

the proper cuts.

A zone scheme can be recognized

by the initial step of the linemen. If every blocker takes the same initial

step in the same initial direction regardless of how the defense is aligned in

front of them, in all likelihood they are blocking on a zone run. Each linemen

is responsible for a lane running at an angle down the field. They continue

down this lane until they find someone to block, letting the adjacent linemen

take care of anyone who slips around their lane. They often go to the ground to cut the legs of a defender, happy to create a pile as long as it gets their man out

of the picture.

Zone running requires smaller,

quicker offensive linemen than normal schemes. They aren’t asked to push their

defenders backwards as much as direct them to the side. The philosophy behind

this scheme is that no defense is perfectly sound, that eventually some

defender will screw up his responsibility and leave a wide open running lane.

It is up to the runner to find this lane and to attack it. A zone running back

has to have excellent vision, and he has to be decisive. He needs to make a

single cut and hit the hole, not wasting time dancing while the defenders run

around his linemen. Every team in the league runs some version of a zone

rushing scheme, but some teams do it more than others. Mike Shanahan

is often associated with this scheme, and coordinators and coaches who descend

from his coaching tree usually run a scheme heavy with zone rushing plays.

Option Route

An option route is a crucial part

of every passing offense in the league, but most fans (and some commentators)

don’t seem to understand what is going on. A number of passing plays called in

the NFL are more complex than simply telling each receiver which route to run

and letting the quarterback choose from between them. It is common to have one

or two receivers in each play with the option of running multiple routes

depending on what they read from the coverage. The quarterback is responsible

for reading the coverage as well, and provided they both make the same read they should

be able to find a hole in the defense for an easy completion.

There are many varieties of

option routes in the NFL. Most hot reads are some form of option route,

trusting that the receiver will see the same pressure as the quarterback and

cut off his route to catch a quick pass. Back shoulder throws are often read

plays, requiring a receiver to stop a deep route if he can’t beat the defender

over the top. There are also more subtle variations in which a receiver will

adjust the angle of his route to find a gap between defenders or stop running

to sit down in a hole in the defense’s coverage.

Option routes are useful, but

they are also dangerous. If the quarterback and the receiver read the coverage

differently, the pass will end up nowhere near the receiver. A

defender reading the quarterback’s eyes can drop right beneath the throw for an

uncontested interception. Even if there is no defender around, it is common to

see quarterbacks throw balls with no hope of being caught. On a good offense

with smart receivers and a smart quarterback, option routes can be impossible

to stop. Otherwise, they can absolutely kill an offense’s attempts to move the

ball.

Read Option

An NFL offense is at an inherent

disadvantage against a defense on running plays. The defense always has eleven

players responsible for chasing down the ball carrier, but the offense essentially loses the quarterback the moment he hands off the ball. Even if every blocker successfully takes care of one of the

defenders, that still leaves the running back alone versus two unblocked

defenders.

The option has long been a way to

even up the number game. In the past it dominated at the high school and

college level in a more traditional form. The quarterback would receive the

snap and run parallel to the line of scrimmage. The offensive line would not

block one of the defenders, usually the end man on the line of scrimmage, and

would leave him for the quarterback to read. If he goes after the ball, the

quarterback pitches to the running back racing beside him. If he goes after the

running back, the quarterback keeps the ball and cuts up the field. In this

way, the quarterback essentially takes one of the opposing defenders out of the

play, serving as a sort of tenth blocker for the offense.

The option never found much

success in the NFL for one simple reason: the health of the quarterback.

Passing the ball has always been more effective than running it, and with only

thirty-two teams every team can have hope of finding a high quality passer. But

passing quarterbacks are usually not great rushing quarterbacks, and they often

aren’t built to take full speed collisions. The traditional option requires the

quarterback to hold on to the ball until the defender is right on top of him,

and there is no way for a quarterback to avoid or protect himself from a major

hit. Against the large and fast defenders that populate NFL teams, an injury is

inevitable.

The read option has changed

things. Like the traditional option, the read option uses the quarterback as a

sort of blocker to eliminate an unblocked player from the play. Unlike the

traditional option, the read option allows the quarterback to make the decision

farther back from the line, where he doesn’t have to fear major collisions. The

offensive line again leaves a defender unblocked, and the quarterback reads

this player’s response to decide where to send the ball. If the defender comes

at him, he hands it to the running back on a sweep away from the defender. If

he crashes down the line, the quarterback keeps the ball and runs through the

lane departed by the defender. The read option has all the same fundamentals as

the traditional version, and it does so without putting the quarterback in

harm’s way.

Jet Sweep

The jet sweep is another new

wrinkle steadily moving into NFL offenses. Every offense over the past few

decades has included some variety of the end around, where a wide receiver

comes running from one side of the field back around the quarterback and the

running back to take a handoff wide in the opposite direction. This play is

used infrequently to try to catch the defense off guard, and if the defense is

not prepared to keep contain it usually results in a large gain. But the defense also has plenty of time to react, and if they can keep contain the play is usually bottled up for a large loss.

The jet sweep involves similar

action to an end around, but it does it in a much more efficient way. On a jet

sweep, a receiver lined up off the line comes in motion towards the quarterback

parallel to the line of scrimmage. The ball is snapped just before he can cross

to the other side of the formation, and the quarterback hands it off

immediately by spinning from under center or handing it forward from shotgun.

The receiver is already moving at full speed at this point, and it takes him

only a few short steps to flank the defensive players in the box and turn

upfield.

The advantage of the jet sweep is

the speed with which it is run. The receiver is traveling at a full sprint by

the time he receives the ball, and no one from the backside or the middle of

the field has any chance of catching him before he reaches the edge. The only

players who can stop this play are the linemen and linebackers to the play

side, and they have to react extremely quickly to contain the runner and close

down the lanes to the inside. Even if a contain man can prevent the runner from

gaining the edge, he usually can’t collapse the blockers quickly enough to

close down a cutback lane to the inside.

The only way to stop the jet

sweep is for the defense to begin moving before the ball is snapped, but this

leads to plenty of problems on its own. The jet sweep motion is often used as a

decoy to force the defense to react, opening holes for the running game or

seams for passes. The jet sweep is a very successful part of an offense, and

there is no simple way to shut it down. Its role will only continue to expand

over the next few years.

Packaged Play

I touched on this some on

Wednesday when discussing Teddy Bridgewater, but I’ll go into more detail here.

Packaged plays are the NFL’s most popular new trend, a twist on the ideas of

the traditional option schemes. Like the read option, packaged plays allow the

quarterback the versatility of the option without risking undue harm. On a

packaged play, the quarterback has the choice to either hand the ball off or throw

a quick pass to one of his receivers. He makes this decision based on reads

before the snap and reads while the play is still ongoing. If a linebacker

crashes hard against the run, this opens a lane for a tight end up the seam. If

a safety playing over the slot receiver runs into the box, this receiver is

open for a quick screen or slant. The rest of the team still treats this as a

running play, and if the defenders sit back in their passing lanes it is very

easy for the offensive line to overwhelm them while the quarterback hands the

ball off to the running back.

Packaged plays are incredibly

difficult to defend, for all the same reasons as the option. They take away the

numerical advantage possessed by the defense, forcing defenders to beat the man

in front of them in order to stop the play. Because the quarterback has the

freedom to make up his mind after the ball is snapped, it is difficult for the

defense to disguise their scheme and fool him. The only risk the offense runs

is that the pass won’t come out quickly enough and that their linemen will end

up too far downfield. But referees are slow to throw the flag on these plays,

and offenses can get away with almost anything provided the quarterback doesn’t

take too long to make his decision.

Swinging Gate

This isn’t technically offense,

but I think it fits here nonetheless. The swinging gate is a scheme used on

special teams—primarily on extra points, but also occasionally on field goals

and punts—to try to create an advantage over the defense using formations. It

is a scheme that is still gaining traction in the NFL, after achieving

popularity in college and high school. There isn’t any particular reason for

this slowness, besides the occasional confusion and mockery it provokes with

the fans and the media.

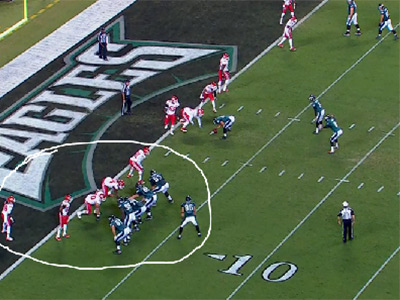

The image above displays a common

variety of the swinging gate extra point. The long snapper, holder, and kicker

remain in the center of the field, but the rest of the team lines up in much

different positions than what you would normally see. The tight

end and wing on the right side line up split towards the sideline, while

everyone else lines up in a tight formation to the left. The player responsible

for receiving the snap—usually the holder—makes a quick read based on how the

defense responds. In the case shown above, the defense only sends out five

players out to match the offense’s six. If he sees a mismatch, the holder has

the ability to snap the ball and throw it quickly to the advantageous position

in an attempt to score two points. If no mismatch presents itself, the kicking

team will shift into a standard kicking set and take the extra point.

Besides the outsider responses I

mentioned above, there are a couple reasons the swinging gate hasn’t caught on

at the NFL level. The most important is probably discipline. NFL players are a

lot smarter and a lot better prepared than players at the high school and

college level, and if the swinging gate is run often enough they will

eventually adjust to eliminate any sort of advantage. Teams that run the

swinging gate would end up kicking on every play, and installing a scheme they

would never find any use for would just be a waste of practice time.

The rules of the NFL also limit

the usefulness of this scheme. In most high school leagues, teams are allowed

to place as many eligible players on the field when lining up for a kick or for

a punt. This gives them more versatility in their formations, allowing them to

do sneaky things like sneaking the left wing onto the line and moving the right

tight end off of it, which would then make the long snapper an eligible

receiver. There is no way to accomplish this in the NFL without declaring the

long snapper as an eligible receiver, which would clue in the defense. The

swinging gate isn’t used in the NFL because it doesn’t present as great an

advantage as it does in the lower levels, but pulling it out every now and then

could provide a small bonus to an offense.

No comments:

Post a Comment