Last

week I went through the best offensive players available in the draft, and this

week I've moved on to the defensive side of the ball. I've broken the available

players into four categories based not on explicit positions but on how they

will be used in the NFL: Defensive Backs, Interior Linemen, Linebackers, and

Pass Rushers.

In each

position group it seems the common theme is the choice between present skill

and athletic potential. More often than not I found myself siding with those

who have already shown the technique to play in the NFL, but this isn't a

condemnation of players whose value is based on their athleticism. It is highly

likely that some of my lesser ranked prospects will turn out to be the best,

but because of the risk involved I couldn't justify putting them above their

more proven peers.

Again, all the film I watched came from the wonderful website Draft Breakdown. You should really check it out sometime if you have interest in the draft.

Again, all the film I watched came from the wonderful website Draft Breakdown. You should really check it out sometime if you have interest in the draft.

Defensive Backs

Darqueze Dennard, CB, Michigan State

Dennard has been steadily falling

as the pre-draft process has gone along, as one would expect from a player who

can’t match up athletically with his peers. After being a top ten pick in some

early projections, a 4.51 time in the 40 yard dash has knocked him potentially

out of the top twenty. Of course, this isn’t new information. Dennard has

always been slow for a top cornerback, and it shows on the field. He doesn’t

have the ability to chase down receivers when he is beaten, so he takes care

not to let himself be beaten. His technique is excellent, and he is quick to

turn his hips when he sees a receiver running deep. The downside is that he

plays without aggression, and he can be beaten underneath by well run out

patterns and curls.

What puts Dennard above the other

cornerbacks is his physicality. He enjoys throwing himself into the backfield

as a run defender, and he is an excellent tackler in the open field. He doesn't bring this physical presence to his coverage, though he will occasionally use

his hands to prevent a receiver from crossing his face. In college he preferred

to turn and run with a receiver rather than trying to stonewall him at the

line, but I think he has that capability if properly coached in the NFL. These

tools together give him the ability to bump inside and play in the slot,

versatility the other cornerbacks in the draft lack.

Ha Ha

Clinton-Dix, S, Alabama

Clinton-Dix may be the most

fundamentally sound player available in this draft. Surrounded by talent at Alabama, he was never

required to make flashy, game altering plays. His job was usually to sit back

in a deep zone and to protect over the top while his teammates controlled the

game up front. He never allows receivers to get behind him, and he is a sure

tackler in the open field, whether it is against receivers after the catch or

moving up in run support. He always breaks down before making a tackle, and he

never attempts to just knock a player out instead of wrapping him up.

The concern I have with

Clinton-Dix is how he will transition to the NFL, where he won’t be constantly

surrounded by top notch defensive talent. If a team looks to him to make big

plays, they will wind up disappointed. He doesn’t cover ground particularly

well, leaving him a couple steps behind where he would need to be to intercept

deep throws. Though his balanced approach against the run prevents broken

tackles, it slows him down and allows ball carriers to pick up an extra couple

yards on each run. These concerns are worth addressing, but they aren’t worth

too much thought. There is nothing wrong with having a solid, reliable safety

in the NFL, and that is what Clinton-Dix will be.

Bradley Roby, CB, Ohio State

Roby may be the most difficult

player to figure out in the draft. In 2012 he looked like a future superstar, a

cornerback who would fly around the field making plays for years to come. He

made incredible breaks on the ball, had the speed to make up for any errors he

committed, and had wide receiver instincts for playing the ball when it was in

the air. He was every bit as committed to stopping the run as Dennard, even if

he occasionally struggled to get off blockers. Everything we saw from Roby

during his sophomore season suggested that he would be a top ten pick when he

was finally eligible to come out.

And then 2013 happened. Ohio State’s

defense was up and down throughout the season, and Roby’s inconsistency had a

great deal to do with their struggles. He still flashed the brilliance that

made him one of the nation’s best players in 2012, but teams became smarter at

exploiting his aggression with double moves. He was asked to play more zone

coverage, and he frequently became lost drifting in space while receivers ran

past him. But he showed enough to suggest he can return to the dominant

player he was two years ago, and a strong performance at the combine has pushed

him back into the first round. He is the best in the draft at pressing

receivers and breaking on the football, and if properly coached he has the

highest upside of any of the top cornerbacks.

Calvin Pryor, S, Louisville

Clinton-Dix may lack flashiness

at the safety position, but Pryor more than makes up for it. Though both

players ran identical times of 4.58 in the 40 at the combine, Pryor plays

significantly faster. He flies all over the field in both the run

and the pass, operating on an instinctive level that often takes him outside

the defensive scheme. This leads to big plays, but it also causes problems. He

will sometimes jump a route, leaving his zone to run at an already covered

receiver. For this reason he didn’t spend a great deal of time playing in a

deep zone at Louisville,

instead covering the flats or matched up man to man on a slot receiver. This

versatility is a bonus in the NFL, but it means little unless he can learn to

be more disciplined in deep coverage.

His frantic aggression is even

more noticeable in the running game. He flies towards the line the moment he

reads run, hitting blockers and ball carriers at a dead sprint. This allows him

to make plays nearer to the line of scrimmage than Clinton-Dix does, but it

also leads to him playing out of control at times. He will sometimes run to a

gap only for the running back to cut the opposite way, taking himself out of

the play. He also has a habit of throwing himself full speed into a ball

carrier’s legs rather than breaking down and wrapping up, leading to missed

tackles. Like Roby, Pryor is a bit of a project. But he has plenty of ability to

bring excitement and game changing plays to a defense.

Justin Gilbert, CB, Oklahoma State

In terms of raw size and

athleticism, Gilbert stands above the rest of the cornerbacks in the draft. His

height is only slightly above average, but his long arms can close down a lot

of throwing windows. Toss in a 4.37 time in the 40 and the agility of a punt

returner, and you have an athletic package that leaves most coaches and fans

drooling. If his coverage skills were anything above average, we would be looking

at one of the best players in the draft.

The problem is that Gilbert

doesn’t come close to matching either Roby or Dennard in coverage ability. The

speed to catch up to a receiver on a blown coverage is a plus, but a cornerback

who is forced to rely on it multiple times each game likely suffers from poor

technique. A fast receiver can run past Gilbert before he gets his hips turned

around, and despite his size he rarely uses his hands to impede a receiver’s

progress. He brings no physical presence to the pass defense, and he is

nonexistent against the run. He lacks Roby’s ability to make sharp breaks on

the ball, and he doesn’t come close to matching Dennard’s technique. This means

that he can be beaten both underneath and over the top. His length and athleticism

allow him to shrink these windows more than most cornerbacks, but the windows

still exist for well placed and well timed throws to exploit. For these

reasons, I would not even consider selecting Gilbert until late in the first

round.

Interior Linemen

Aaron Donald, DT, Pittsburgh

The best defensive player in

college football last season had one of the best performances of any player at the combine, and yet he still may not be

selected in the top ten. Donald is undersized at only six feet tall and 285

pounds, and he has a bit of an unfair reputation as a player who only succeeds

through pure effort. The word most often used to describe his play is

‘relentless’, and somehow this has become a negative for him. People become so

engrossed in how hard he tries on each play that they overlook how talented and

skilled he is as a football player.

Donald dominated college football

last year due to a rare combination of athleticism and technique. He gets off

the ball quickly, and once engaged with a blocker he has a number of tools he

can use to beat him. He has shown a swim move, a bull rush, and a spin move,

but his most common tactic is to simply swat the blocker’s hands away before

using his speed to run past. Though he is smaller than desirable, he has long

arms that help him when hand fighting with linemen. He doesn’t have the length to play

defensive end in the 4-3 or the 3-4, and he doesn’t have the size to play nose

tackle in either front. This isn’t the problem it was a couple years ago, as

teams have gotten smarter at playing varied fronts that work to their players’

strengths. Donald should go in the top ten, and if he falls past that he will

be one of the steals of the draft.

Ra’Shede Hageman, DE/DT, Minnesota

Relentless effort is the most

commonly praised part of Donald’s game, and it is the most commonly criticized

part of Hageman’s. An athletic marvel, Hageman shows flashes of dominance

interspersed with long periods of apparent indifference. He rarely bothers with

backside pursuit, and he is content to hold his ground against a double team

rather than trying to fight through it. He wasn’t an every down player at Minnesota (though this

was likely because the coaches liked to rotate all their defensive linemen) and

he rarely took over games as one would expect of a player of his abilities.

All that said, the flashes of

excellence he showed were staggering, more than enough to push him up into the

first round. He always comes off the ball hard, knocking offensive linemen a

yard backwards with his initial contact. He possesses no moves to disengage

from blockers, but every now and then he can break free by pure strength alone

and swallow a ball carrier in the backfield. As a pass rusher he only ever

tries a bull rush, and once past the initial surge the only thing he can do is

bat down passes. Coaches look at a player like Hageman who can dominate on pure

talent alone and wonder what he could do if taught how to play with technique.

Whether he is capable of being coached remains the crucial question, and it is

something teams will have to figure out during their pre-draft meetings with

him.

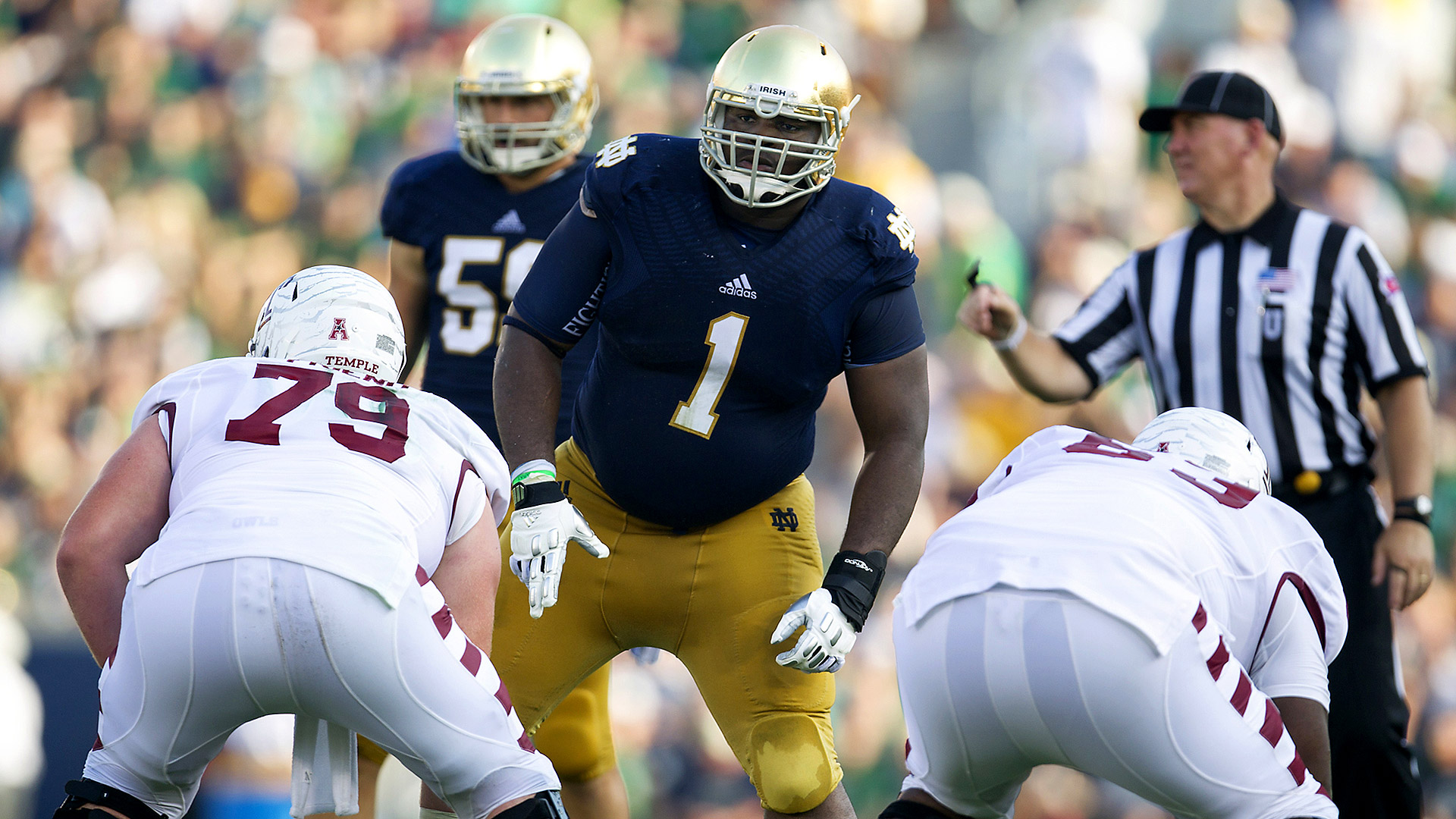

Louis Nix, DT, Notre Dame

Nix has a reputation as the

premier run-stuffer in the draft, so I was surprised to see the value he brings

as a pass rusher. He isn’t particularly quick off the ball or the through the

gaps, but he plays well with leverage, getting beneath offensive linemen and

using his strength to twist their shoulders so he can get past them. If single

blocked, he can turn a lineman around and create pressure in a passer’s face.

Unfortunately, he doesn’t actually disengage from the blocker, and good

quarterbacks will be able to recognize this and step to the side the offensive

lineman has sealed off. Nix can disrupt a passing play, but he isn’t going to

collect a lot of sacks.

In a lot of ways, Nix is a

similar player to Hageman. He isn’t nearly as quick or as strong, but he has a

similar style of flashing dominance just often enough to be intriguing. He

draws a lot of double teams but rarely fights past them, and his game relies

almost solely on his ability to bull rush a lineman. He uses his hands to

disengage more often than Hageman, but this is still a weakness in his game. Right

now I would say that he is the superior player, but I have him ranked lower

because of a lack of positional versatility. Both players can play nose tackle

in either a 4-3 or a 3-4, but Hageman has the ability to slide outside and

contribute as an under tackle or a 3-4 defensive end. Nix is only capable of

playing in the heart of the defensive line, a position whose value has

diminished over the past few years.

Timmy Jernigan, DT, Florida State

This seems strange to say about a

defensive tackle, but Jernigan shows very little interest in playing against

the run. He comes off the ball almost straight up, engaging the blocker at the

line of scrimmage and not bothering to disengage unless he reads pass. He is

frequently driven a couple yards backwards by the initial surge, and even if he

does get off his blocker he rarely bothers pursuing a play going away from him.

Altogether, Jernigan is one of the worst defensive tackles I have ever seen

against the run.

It is fortunate then that he has

so much talent as a pass rusher. Though he can’t match the athleticism or

strength of Hageman and Nix, he has a number of moves he can use to break free

from blockers. He swats their hands away to free himself from the initial

contact, and he possesses a devastating swim move that gets him unchecked into

the backfield. He would be even more dangerous if he came off the ball quicker

and stayed low as he tried to shoot through the gaps, but his current skills

will catch the eyes of the teams that scout him. Jernigan is likely a second round

prospect, but he has the potential to slip up into the first round if a team

falls in love with his pass rushing abilities.

Linebackers

CJ Mosley, LB, Alabama

Mosley is the prototypical run

stuffing middle linebacker. He plays physical, downhill style, and he is at his

best between the tackles. From the moment he recognizes a running play, he attacks

towards the line of scrimmage and into the backfield. He has the strength to

plug up blockers in the hole, and he excels at

fighting past linemen trying to reach him on the second level. Ten or twenty

years ago he would have been a top ten pick in the draft, but in the modern NFL

a linebacker needs to be able to do more than stuff up the interior running

game.

Mosley is a solid player against

the pass, and it shouldn’t be necessary to take him off the field in passing

situations. He has a good sense of how to drop underneath the seam and slant

routes, and he does a good job playing the ball in the air (even if he

struggles to catch it.) He will be useful in the passing game, and no team

should avoid taking him because of this. The biggest concern with Mosley is his

lack of speed. While he excels within the tackle box, he rarely makes plays

outside of it. Once a runner gets outside he needs to take a wide angle just to

catch him, and he usually cannot become involved on a play at the sidelines

until the runner is already ten yards downfield. If I’m looking to invest a top

twenty pick in a linebacker, I want someone who will play from sideline

to sideline. As talented as Mosley is, he will never be that player.

Ryan Shazier, LB, Ohio State

Like most projections, I have

Shazier ranked below Mosley among inside linebackers. He is a less polished

overall player, and his upside is only slightly higher than Mosley’s. But I

don’t think it would necessarily be a mistake if he was the first linebacker to

go off the board. He and Mosley are very different players—everything I

criticized about Mosley is something Shazier excels at—and it is undeniable that Shazier is better suited for the modern NFL. He is significantly

more athletic, running an absurd 4.38 in the 40 yard dash. He regularly chases

runners down from behind, and he covers ground from sideline to sideline as

well as any linebacker I’ve seen.

I have Shazier ranked lower

because, even though he is more suited to playing linebacker in the modern NFL,

he falls short in more areas than Mosley. Inside the tackle box he can be

overwhelmed by blockers and caught up in the wash. He isn’t as sure a tackler

as Mosley, and he can be knocked backwards by a powerful runner. He has bulked

up some since leaving college, but it remains to be seen whether he can adjust

to the physicality of playing inside linebacker in the NFL. These shortcomings

are enough to drop him to the end of the first round, where some team will fall

in love with his instincts and athleticism.

Pass Rusher

Jadeveon Clowney, DE, South

Carolina

The 2012 version of Clowney would

be the undisputed top player available in this draft. The lesser 2013 version

would still go in the top ten. The narrative of his decline has been greatly

exaggerated over the past year, and you only need to look at the tape to

realize what Clowney is capable of offering. Even with minimal effort he was

always the best player on the field, and he still flashed enough moments of

dominance to let everyone know what he is capable of. If I was just evaluating

his 2013 season and his combine results I would see an athletic monster with

great potential as a pass rusher, provided he can develop an array of secondary

pass rush moves.

But we have already seen that he

has these moves. We saw them for a full season, and even though he spent most

of last year surrendering once his initial rush was handled, I have complete

faith that he is capable of returning to the player he was. He has always had

an explosive first step that allows him to beat a tackle around the edge, but

what truly sets him apart is his underrated ability to win against a blocker

after the initial surge is handled. He strikes with his hands first to create

separation then uses his strength to control the man in front of him. As

explosive as he is, he needs only a moment of leverage to swipe away a

blocker’s arms and race past him. Clowney is a complete football player, both

as a pass rusher and a run defender. He plays with aggression and discipline,

pursuing plays from behind while still doing his job to keep contain. I have no

complaints about his game, only about his attitude, which I am in no position

to evaluate. If he can commit to playing football professionally, he will be the best player to come out of this draft.

Khalil Mack, OLB, Buffalo

Mack did just about everything

for Buffalo on

defense last year, but he was at his best as a pass rusher. He only rushed on

about half the defensive plays, but when he did he was a nightmare in the

backfield. His lateral quickness allows him to sidestep blockers, and he does a

fantastic job keeping himself low to slide underneath the arms of a taller

tackle. His initial get-off was slowed occasionally by his stance, which was

more balanced as one would expect from a traditional linebacker. In the NFL he will spend most of his time set up as a pass rusher, and it will be even easier for him to rush around

the edge. When he did line up in a pass rushing stance in college, he was every

bit as quick up the field as you would like to see from an elite pass rusher.

Mack’s skill with his hands isn’t

quite on the same level as Clowney’s, but it is still well above average. It is

almost impossible to cut him, as he uses his hands to push aside anyone who

tries diving at his knees. It is rare to see a blocker truly control him, and

even if a lineman gets his hands into Mack’s chest his position is not secure.

Lateral quickness allows Mack to force the blocker’s arms outside his frame to

draw a lot of holding penalties, and strong hands give him the ability to

disengage at will. His best pass rush move is probably his bull rush. He keeps

his hips low as he drives the lineman deep into the backfield, and once he is

within reach of the quarterback he has no trouble casting the blocker aside.

Mack will need some time at the NFL level to adjust to his role as a full time

pass rusher, but once he does he will be one of the best in the league.

Anthony Barr, DE/OLB, UCLA

Nothing can be written about Barr

without mentioning that he was a running back just two years ago, before the

UCLA coaches decided to test his talents on the other side of the ball. Since

then, his draft stock has faced a similarly tumultuous path. He spent most of last

season as a projected top ten pick before falling in early projections, only to

rise back into the top ten over the past few weeks. This isn’t surprising from

a player who looks like an athletic freak on the field but struggled at the

combine, who still often looks like he doesn’t know how to play the position

yet can dominate on the edge.

Barr is more polished than you would expect from someone still

learning the position, but he still has lapses during which he clearly looks

like a running back playing linebacker. His jump off the ball is adequate, but

he doesn’t have the instant acceleration out of a two point stance to run

around the edge as a stand up linebacker. He is more effective when he can

start slow, get the tackle into a set position, then accelerate past him into

the backfield. He doesn’t possess many other moves, but when he gets his hands

up and extended he can control the blocker in front of him. This applies just

as much in the run game as it does in the pass game, and he shows the ability

to be a dominant two way player. He will need more development than either of

the two pass rushers above him, but it would not be ridiculous for a team to

snag him in the top ten.

Dee Ford, DE/OLB, Auburn

Ford is the best bet for a team

hoping to find an impact pass rusher late in the first round. Though he lacks

the athleticism and refinement of the higher ranked players, Ford has the

ability to be a dangerous pass rusher in the NFL. His game is predicated on

quickness, on his ability to beat a tackle around the edge with a traditional

speed rush. He will occasionally bow too far outwards on this rush, giving the

quarterback a lane to step up behind him. He will need to get stronger to

prevent this in the NFL, and he will need to learn to keep himself lower to

play with better leverage on a blocker.

Where Ford clearly falls short of

elite players like Clowney and Mack is in technique. He has a few moves he can

use that play off his speed rush—every so often he displays a nice jab step to

the inside or the outside in order to get a tackle off balance—but he lacks the

secondary moves of an elite pass rusher. He allows blockers to get into his body

too easily and rarely uses his hands to knock them away. The only technique

that can succeed without the hands is a spin move, and Ford’s attempts at this

were laughable failures. These techniques can certainly be taught at the next

level, but they knock him a notch below the more polished options at the top of

the draft.

Kony Ealy, DE, Missouri

As a prospect Ealy is on a

similar level to Ford, though they are very different players. Ealy isn’t

particularly quick, and he rarely beats pass protectors with a speed rush.

Instead he relies on his strength. He can sometimes get beneath a tackle and

get his outside shoulder turned to open a lane to the quarterback, but he is

much better as an interior rusher. For these reasons he may project better as a

3-4 defensive end, though he will have to add some weight to play that

position. He splits double teams well as a pass rusher, but he doesn’t hold his

ground well against two run blocking offensive linemen.

Ealy’s shortcomings are similar

to Ford’s. He doesn’t use his hands particularly well, and he has no counters

to using his strength to push past poorly positioned linemen. He doesn’t

possess a particularly dangerous bull rush, and if a blocker can get himself in

good position with a stable base, Ealy is essentially handled. He is better as

a run defender than most of the other pass rushers in the class, but he needs

to improve as a defender at the point of attack. When given the chance to chase

a play down from behind he is both relentless and disciplined, but when a team

runs straight at him he offers little resistance. Ealy has significantly less

upside than any of the four I’ve listed above him, but he is probably still

worthy of a late first round pick.

No comments:

Post a Comment